(This is long and deals with the intersection of geography and football. You have been warned.)

When Iowa State was on the verge of falling into athletics oblivion a year ago (again), I wrote in The Des Moines Register about external factors working against the teams, the university, and the state as a whole: population shifts and media markets. I’m going to expound more on that here. See also Andy Staples’ article earlier this week about TV and college football.

There’s a reason besides those six consecutive crystal footballs that the SEC can look at everyone else and say, “Scoreboard.” Its teams aren’t only winning with skill, its states are winning with numbers. (Well, skill and the Big 12 circular firing squad.)

(Additional census information here [Flash] and here [text].)

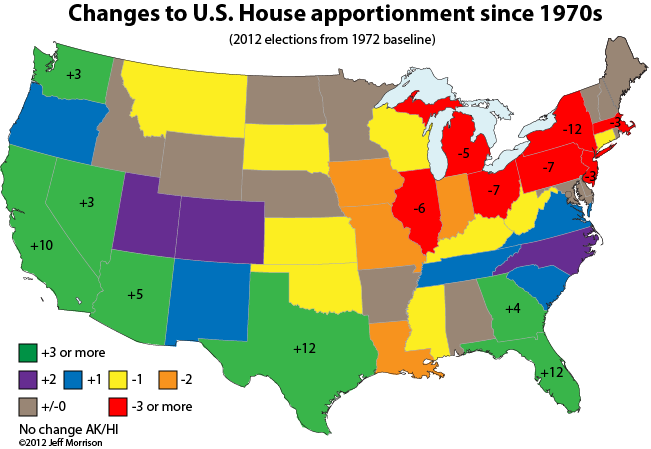

This analysis starts with the U.S. House congressional apportionment from the 1970s. It’s a good place to start, as it’s just after the Texas national championship of 1969 — the last won by an all-white football team — and the 1971 Nebraska-Oklahoma Game of the Century. It concentrates on the predecessor and existing versions of the top four football conferences in the country.

A note: This post is exclusively about populations. It does not factor in such things as cultural differences, spring high school football, college vs. pros, or weather, all of which also have their own part in this tectonic shift.

In 1971, Iowa State finished an 8-4 season with its only regular-season losses being to the top three teams in the country — the aforementioned Nebraska and Oklahoma teams, plus Colorado. The next year’s post-census apportionment looked like this by conference and state:

- 28, Southwest Conference (AR, TX)

- 35, Big Eight (CO, IA, KS, MO, NE, OK)

- 54, Pacific-8 (CA, OR, WA)

- 60, Southeastern Conference (AL, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, TN)

- 100, Big Ten (IL, IN, IA, MI, MN, OH, WI)

Iowa is the only state divided between two of the selected conferences at this point. In the rest, there’s one big state school, the two biggest in the state are running in the same circles, or the other major school grew as an independent. (The state of Indiana is its own special creature, but the Big Ten pines so much for Notre Dame this is like throwing them a bone.)

What about the ACC? The flippant answer: It’s a basketball conference. More serious answers: It hasn’t been relevant in the national championship picture for over a decade. The larger proportion of private schools in the conference make the dynamic different, especially when it comes to fanbase and state support. It is largely in areas that pay less attention to college football. Its most recent TV contracts show it is not valued as much as the other four conferences. Finally, its overlap with the SEC and inclusion of the Big East All-Stars complicates the model too much.

You’re indiscriminately including entire states. That’s not fair. Short answer: Maybe. Long answer: While not perfect, I think it is a decent measurement for/proxy of “where the people are,” especially since I don’t have access to what the Nielsen numbers were back then. Bigger states have bigger/more media markets, which become the Holy Grail of television contracts after the end of the NCAA monopoly and especially in the 21st century. Without markets, you better hope your team already earned “mind-share” from past victories. Remember, you’re either a market or a brand. This is why the Jim Walden era was a really bad time for Iowa State to suck, and why Kansas State needs Bill Snyder to keep pulling those rabbits out of his wizard hat.

The people in the markets don’t have to watch the games, of course. The conference media deal-makers merely need a critical mass (see: Mediacom and Comcast vs. Big Ten Network).

The 1990s saw the finalizations of moves that were, until the beginning of this decade, the status quo in the selected conferences. The Arizona schools moved to the Pac in 1978, Arkansas and South Carolina began SEC play in 1992, and Penn State started playing Big Ten football in 1993. Population shifts were very much on the mind of the Big Eight when it looked to Texas — notice that Colorado is its only state that made gains in 40 years. After the beginning of the Big 12 Conference in 1996, this is how it looked for Bill Clinton’s second term and the 2000 election:

- 63, Big 12 (CO, IA, KS, MO, NE, OK, TX)

- 72, Pac-10 (AZ, CA, OR, WA)

- 78, SEC (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, SC, TN)

- 108, Big Ten (IL, IN, IA, MI, MN, OH, PA, WI)

This is the high-water mark of the Big Ten. Ohio State’s 2002 BCS championship is the only one north of the Mason-Dixon and Missouri Compromise lines.

In the early 2010s, the script finishes flipping — for now at least. In between the 2010 census and its effects on Congress, Colorado, Missouri, Nebraska, Texas A&M, Utah, and West Virginia played musical chairs. This fall, this is how the apportionment plays out:

- 52, Big 12 (IA, KS, OK, TX, WV)

- 88, Pac-12 (AZ, CA, CO, OR, UT, WA)

- 92, SEC excluding Texas

- 98, Big Ten (IL, IN, IA, MI, MN, NE, OH, PA, WI)

- 128, SEC (AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, LA, MS, MO, SC, TN, TX)

Note, also, that we’ve gone from dealing with 24 states (1 doubled-up) in 1972 to 29 (2 doubled-up) in 2012.

Here’s the biggest takeaway of those numbers: Even with the additions of Pennsylvania and Nebraska, the Big Ten has fewer House seats than it did in 1970. The SEC added four states and, even without the 800-pound gorilla of Texas, went from 3/5 the size of the Big Ten to within shouting distance. The Texas-population-dominated Big 12, meanwhile, remains the smallest numbers-wise and punches above its weight with a rabid fanbase. There’s a reason Iowa State recruiting has a pipeline into Florida.

The more people living in the SEC’s footprint, the more people likely to tune in to those games and/or have those games thrust upon their cable lineup. It is a tug-of-war between the Midwest diaspora and multi-generational SEC-team fans. The South and Southwest have been rising for the past 40 years. The college athletics landscape is just now beginning to reflect it.