Southern Page County did its damnedest to put itself on a paved path to prosperity.

The Highway 333 Association formed in the summer of 1959 with the goal of getting the road from US 275 near Hamburg to US 71 at Braddyville hard-surfaced. A delegation of 61 people went the 180 miles to Ames to have their concerns heard, and reading about that meeting will take you to a time far different from our own.

AMES, Ia. — A farm wife said Wednesday she doesn’t dare wear white gloves while riding on dusty Highway 333.

“The gloves would get dirty immediately,” Mrs. Dale Athen of Hamburg told the Iowa Highway Commission. “I have to carry my gloves in my purse if I want to keep them clean.”

— “White-Glove Objection to Highway 333,” Des Moines Register, September 10, 1959

It had been 19½ years since a delegation from Shenandoah had asked for IA 208 and 333 to be blacktopped and got nothing. The result this time was scarcely different…with a fractional exception. In the Iowa DOT online construction archives are plans for right-of-way and culverts in 1959 and 1960 along the Goldenrod from the College Springs junction eastward, with no route number. The road was still gravel, but starting in 1961, IA 999 was on the map, hiding in plain sight.

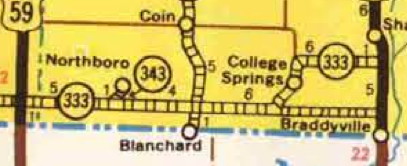

See the gravel marking right above the word “Braddyville”? That’s 999. By the end of 1964 the intersection of IA 208 and 333 was the only location in Iowa where two gravel routes met.

Southern Iowa is full of gently rolling hills. Under those hills — especially in the Des Moines River valley — is an abundance of “soft coal” deposits that contributed to a mining industry that was extinct by World War II. What isn’t abundant is the aggregate needed for highway concrete.

It was found that the gravel that is so plentiful in north-central and northern Iowa is almost entirely lacking in the southern part of the state. Furthermore, ledge rock was found to be almost entirely absent from the southwestern part, and though it is more abundant in the south-central and southeastern parts, even there it is in some places of poor quality or is available only in limited, quantity.

— The Road and Concrete Materials of Southern Iowa (1935)

You can’t get much farther south than a mile from Missouri.

Fremont County got 333 paved west of US 59 in 1964, and as a consequence the state dropped it. The mile east of there would be paved in 1970, giving the highway a “hanging end” for a decade. Page County would not fare nearly as well.

- In 1957, two years before the aforementioned “white-glove” meeting, 333 from US 275 to US 71 was “the longest single stretch [of primary road] still surfaced with gravel and crushed rock.” (Register, September 4)

- In 1961, the Highway 333 Association was told it would be paved in 1965. (The very same night, voters in the two-year-old South Page school district shot down a bond issue for building a new gym at College Springs.) (Clarinda Herald-Journal, September 14)

- In 1971, the state put 333, 343, and 999 down for paving “after 1977”. (Herald-Journal, December 23)

But for the Goldenrod itself, the only sop was bridge replacements, for a situation so dire that the Herald-Journal reported March 14, 1968, that Shenandoah school bus riders had to get out and walk across one of the bridges because of the load limit.

In 1967, the state approved paving the road from College Springs north and east to US 71. It happened a year later, and the segment once known as IA 84 in the original 1920 system was off the state books for good. The remaining 2½ miles from College Springs to the Goldenrod was left as a secret designation.

Or was it?